Timeline of 19th Century Base Ball Events and Matches

The following information represents the best information available to members of the Keystone Base Ball Club of Harrisburg at the time of publication, but is subject to further confirmation by ongoing research by sports historians at a variety of academic institutions, and members of the SABR (the Society for American Baseball Research).

Historical Context:

During the early 19th century, socio-economic developments, especially in metropolitan areas of the northeast, enabled the formation of clubs devoted to the pursuit of avocational pastimes, such as hunting, riding, debating, and, manly/gentlemanly competition in bat and ball games. These ball clubs would meet routinely, some as often as twice weekly, to develop their skills at the game, in accordance with the rules as they knew them. Not surprisingly, these rules, and in fact, even the name assigned the game, varied significantly from place to place. The Massachusetts Game, sometimes called roundball, prevailed in Boston. Townball was the sport of choice in Philadelphia. The New York game, generally accepted as the predecessor to today’s game, was perhaps the best documented in the first half of the 19th century.

July 4, 1833

A loose collection of townball players from Camden, known not so creatively as the Camdens of Camden, New Jersey, meet the more formally organized Olympics of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in what is generally agreed to be the first documented “match”. (A “match” pits two distinct entities against each other, as distinguished from a “game”, in which members of the same organization divide themselves into two teams.) The clubs subsequently merge to form the Olympic Ball Club of Philadelphia, which survived into the late 1880’s. In 1837, the Olympic Club adopted a formal constitution that, in many ways, set the precedent for manly and gentlemanly play when it recognized that field sports could be beneficial and enjoyable for the participants “when exercised with decorum and moderation.” This document included the following penalties for the infractions noted:

Failure to take good care of club equipment – 50 cents

Failure to provide a proper uniform – 25 cents/month

Improper or unauthorized use of club equipment – one dollar

Disobeying an order of the captain – up to one dollar

Failure to take good care of club equipment – 50 cents

Failure to provide a proper uniform – 25 cents/month

Improper or unauthorized use of club equipment – one dollar

Disobeying an order of the captain – up to one dollar

1839 (or was it 1841) – The Doubleday Game and the Mills Commission

During the first several years of the 20th century, former pitcher and sporting goods entrepreneur Albert Goodwill Spalding became embroiled in a public debate with sports journalist Henry Chadwick regarding the origins of the game of base ball. Spalding supported the notion that it was a purely American creation, while Chadwick posited that it was an evolution of the English game known as rounders. To resolve the matter, Spalding created a special commission, headed by Abraham G. Mills (former National League President). James E. Sullivan, then President of the Amateur Athletic Union and publisher of Spalding’s Official Baseball Guides, was also a member of the commission, along with five other baseball notables, selected by Spalding. The Mills Commission solicited documentation of the origins of baseball, but by 1907, had not reached a conclusive decision. During the late summer of 1907, Sullivan circulated a 67 and one-half page report to the other commission members, in which 66 pages supported the notion that base ball was of exclusively American origin. There was no response from the other five commission members, but chairman Mills replied with a letter dated December 30, 1907, in which he stated that “the first known diagram, indicating positions for the players, was drawn by Abner Doubleday in Cooperstown, N.Y., in 1939.” The source for this assertion was an elderly mining engineer, Abner Graves, who submitted two letters to the commission, reporting, in considerable detail, his recollection of an occasion in the spring prior to or following the “Log Cabin and Hard Cider Campaign of General Harrison”, which would have been 1839 or 1841. On April 4, 1905, the Akron Beacon Journal reported that Graves’ letters state that “The American game of base ball was invented by Abner Doubleday of Cooperstown, N.Y.”. . ., the said Abner Doubleday being then a boy pupil of Green’s Select School in Cooperstown, and the same, who as General Abner Doubleday won honor at the battle of Gettysburg in the Civil War . . .”. Fact checking was apparently not a high priority in that time, inasmuch as the Abner Doubleday who later served in the Union Army during the Civil War was attending at the United States Military Academy at West Point – not Green’s Select School – during the time of the reported invention. Subsequent scholarly research has revealed that the less famous Abner Demas Doubleday (a cousin of the more well-known Abner Doubleday), was an 11 year old resident of the Cooperstown area during the time in question, and would have been far more likely to have interacted with the 6 year old Abner Graves. In later years, Graves’ credibility was further compromised when he claimed to have been a Pony Express rider in 1852 (despite the fact that the Pony Express did not exist until 1860), and again, while in his 90’s, when during an argument with his wife regarding the sale of their home, he suffered extreme paranoia, and shot and killed her. Baseball researcher and author David Block has suggested that Graves’ letters might have been written as a practical joke, and, because they brought Graves some measure of fame and notoriety, he never chose to recant. In any case, Al Spalding’s salesmanship prevailed, and the myth that 1839 was the birth year of base ball, and Cooperstown was the birthplace of the national pastime, became cemented in American sports history.

1845 – Alexander Cartwright and the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club

Prior to 1845, a New York City bank clerk and volunteer fire fighter with the Knickerbocker Engine Company No. 12, Alexander Joy Cartwright, played townball at a field on Murray Hill. In 1845, that field became unavailable, and, with others, Cartwright formalized the organization of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club, and began playing the New York game at a site in Hoboken, New Jersey, known as the Elysian Fields. While the Knickerbocker Club was not the first formally organized base ball club in New York, history credits the Knickerbocker Club with being the first club to set down their rules in writing (although this has been disputed). History was also generous to Alexander Cartwright, who was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, and whose Hall of Fame plaque credits him with setting the bases 90 feet apart, establishing the length of a game at 9 innings, and establishing the team size at 9 players. Oddly, a review of the 20 Knickerbocker Rules reveals that rule 4 states that the distance from home to the second base shall be 42 paces, and that the distance from the first base to the third base shall also be 42 paces. The definition of a pace is neither clear nor fixed; this, perhaps appropriately, permits the size of the field to be influenced by the size of the players. It is also interesting that rule 8 states that a game is to consist of 21 counts or aces (what we know as runs), so long as both teams have had played an equal number of hands (outs). Finally, the Knickerbocker Rules make no mention of how many players constitute a full team, and the Knickerbockers were known to play with as few as seven and as many as eleven players. While sports historians note that the 1833 townball match described previously is a documented match between two clubs, a June 19, 1846 match between the Knickerbocker Club and the New York Club is often credited with being the first base ball game, the first documented base ball game, and the first game played by the Knickerbocker Rules. Again, history was generous to the Knickerbocker Club, because neither the first nor the second claim is accurate, and it is generally agreed that the third is also inaccurate. Interestingly, the result of this “First Base Ball Game” was a rather convincing loss, 23-1, by the Knickerbocker club to the much less formally organized New York Club.

Doc Adams and the 1857 Base Ball Convention

Dr. Daniel Lucius Adams was also a member of the Knickerbocker Club, serving as president for six years, and as a club officer for another six years between 1847 and 1861. During his tenure with the club, his knowledge and enthusiasm for the game were apparent, and he was selected to represent the Knickerbocker club at a convention of 14 base ball clubs. The primary purpose of the convention, held in January, 1857, was to standardize the rules of the game (a tacit concession that Cartwright’s rules of 1846 did not codify the game to the extent to which he is given credit). Quickly elected president of the 1857 Base Ball Convention, Doc Adams was successful in promulgating changes to the rules that, in fact, established the distance between the bases as 90 feet; established the number of players as nine per side; and established the length of a game as nine innings. These rules were adopted by the convention, and became the law of the still maturing base ball world. While successful in implementing these rules, Doc Adams was unsuccessful in convincing the convention to eliminate the bound rule, by which a striker was retired if a struck ball, whether fair or foul, was caught on the fly or on the first bound. The bound rule would survive until the 1864 annual meeting of the National Association of Base Ball Players, held in December, 1864. An original copy of the 1857 Laws of Base Ball was re-discovered in late 2015, and again brought to light Doc Adams’ legitimate claim to recognition by the Hall of Fame. Efforts to have him inducted are currently spearheaded by his descendent, Marjorie P. Adams. For recent news about this effort, visit

www.docadamsbaseball.org.

www.docadamsbaseball.org.

July 20, August 17, and September 10, 1858

With the increase in the number of base ball clubs in Brooklyn and New York, it is not surprising that in 1858, the presidents of the Brooklyn Base Ball clubs challenged their New York City counterparts to a three game match of picked nines (all-star teams) for supremacy of the metropolitan area. The games comprising this match would be innovative, in that they would be played on the enclosed grounds of the Fashion Race Course in Flushing, New York. Because the grounds were enclosed, the organizers were able to charge an admission fee for the first time. This provided a revenue stream for the clubs, which enabled them to begin (initially overtly and by 1869, covertly) compensating players for their services. Records do not indicate if $7.00 hot dogs were sold at this game.

July 4, 1862

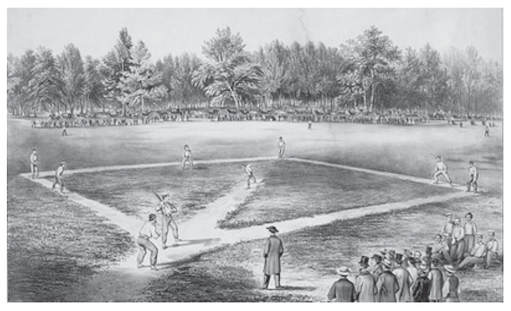

Soon after the start of the American Civil War in April, 1861, the war’s impact on the growth of base ball became apparent. The number of active clubs, which had been rising steadily through the 1850’s, declined sharply, as the young, able-bodied ball players enlisted or were drafted into military service. There is some thinking that as these players move throughout the country with their units, they spread the game that was already becoming known as the national pastime. Most likely, the games were played when soldiers found themselves with time on their hands while in camp, and recalled the spirited and gentlemanly contests that they enjoyed during their civilian days. However, there are several instances of

more formal documentation of ball games that occurred during the war. One such game took place at the Prisoner of War Camp in Salisbury, North Carolina. On this date, still fairly early in the war, the conditions at the camp were tolerable; at least one prisoner recalled that the prisoners were comparatively well fed and treated kindly, and were allowed to exercise in the open air. Records show that on July 4, 1862, the Confederate guards permitted music, a reading of the Declaration of Independence, sack races, foot races, a greased-pig-catching contest, and a base ball game. Otto Boetticher, a military artist and lithographer who had enlisted in the 68th New York Volunteers at the start of the war, was captured early in the war and was imprisoned at Salisbury in 1862. It is quite possible it was the July 4, 1862 game that Boetticher later immortalized in a lithograph titled “Union Prisoners at Salisbury, North Carolina”, which depicted prisoners, and possibly their guards, engaged in a ball game.

more formal documentation of ball games that occurred during the war. One such game took place at the Prisoner of War Camp in Salisbury, North Carolina. On this date, still fairly early in the war, the conditions at the camp were tolerable; at least one prisoner recalled that the prisoners were comparatively well fed and treated kindly, and were allowed to exercise in the open air. Records show that on July 4, 1862, the Confederate guards permitted music, a reading of the Declaration of Independence, sack races, foot races, a greased-pig-catching contest, and a base ball game. Otto Boetticher, a military artist and lithographer who had enlisted in the 68th New York Volunteers at the start of the war, was captured early in the war and was imprisoned at Salisbury in 1862. It is quite possible it was the July 4, 1862 game that Boetticher later immortalized in a lithograph titled “Union Prisoners at Salisbury, North Carolina”, which depicted prisoners, and possibly their guards, engaged in a ball game.

October 14, 1862

A match between the Unions of Morrisania and the Excelsiors of Brooklyn was not particularly noteworthy for the caliber of play, but is remembered as the final game played by base ball’s first superstar, Jim Creighton. Creighton began his base ball career in 1859, as a pitcher for the Niagaras of Brooklyn. He developed a pitching technique that remained just within the limits of the rules, but enabled him to deliver a pitch far faster than his contemporaries. Later in 1859, he joined the Star Club, and in 1860, he joined the Excelsiors of Brooklyn. He developed fairly widespread recognition during the Excelsiors’ tour that included stops in Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington, D.C. During the October 14, 1862 game (according to a report in the Brooklyn Eagle), in one of Creighton’s innings, with a count of two strikes, he swung mightily, but missed, and fell to the ground in obvious discomfort. After a few minutes, he was able to resume play and finished the game. However, after the game, Creighton rapidly became debilitated, and within a few days, passed away, most likely due to internal bleeding or the rupture of his bladder. Several years later, in 1887, journalist Henry Chadwick reported that Creighton had actually injured himself during a cricket match a few days prior to October 14, 1862, but did not realize the severity of his injury, and took no steps to obtain medical assistance. In any case, base ball had lost a talented player who was beloved by New York fans at the time of his passing at the young age of 21.

August 26, 1869

After many years of not so well-concealed financial compensation of base ball players, the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings fielded a team on which all members were paid to play, thereby becoming the first openly, completely professional team. Their proficiency is confirmed by the fact that the club went undefeated during the 1869 season, a streak reportedly consisting of 54 games, of which 29 were contests against clubs on which there were one or more professionally players. An interesting hiccup occurred on August 26, 1869, in a match at the Union Grounds in Cincinnati, with the Unions of Landisburgh, better known as the Haymakers of Troy. The Cincinnati Commercial reported that “The Haymakers, while strong players, are not of good reputation”, with charges of ungentlemanly behavior, bribery, and fixed games associated with the club. Inappropriate behavior by their fans was also alleged. The August 26 contest was apparently typical for the Haymakers, and it is reported that a strong Haymakers supporter, Congressman John Morrissey had placed a $17,000 bet on his team. Both clubs displayed their striking prowess during the first several innings, and after five innings, the score was tied at 17. Cal McVey was the first striker for the Red Stockings in the sixth inning; he sent a foul ball spinning to Haymaker catcher Bill Craver. Reports are not conclusive, but it is currently believed that Craver lunged for the ball, came up with a handful of gravel, but soon grasped the ball, and asked umpire John Brockway, “How’s that”. Brockway ruled (probably accurately) that the ball had bounced twice. However, Haymaker club president James McKeon stormed the field to contest the call, and, when unsuccessful in having the call reversed, removed the Haymakers from the field. The umpire subsequently declared the Red Stockings the victor, but this decision was subsequently overruled by the National Association of Base Ball Players, which declared the outcome a tie (despite the fact that the rules of the day called for a forfeit in the event one club was ready to play the other failed to take the field). In either case, the Red Stockings remained undefeated, and completed the season with no losses. In fact, they did not lose until June 14, 1870.